Luzee doesn’t treat music as content, nor as a product to be optimised.

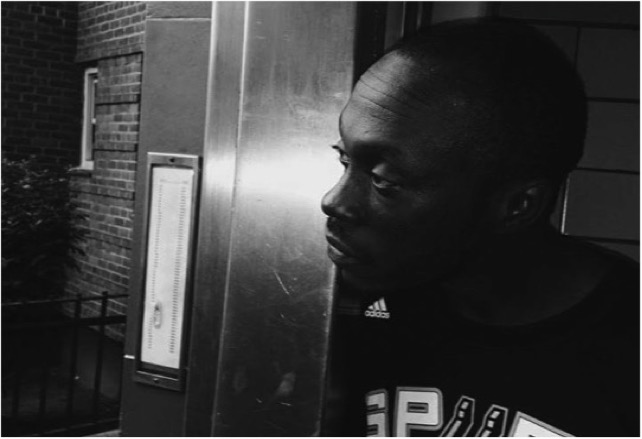

Davide Luzi, also known as Luzee, is a name relatively new to the Italian beat-making scene.

Musician, polyinstrumentalist, and avid digger, his work sits where listening is still an active practice, where sound carries memory, and rhythm is approached as a form of research rather than decoration.

With Afro Sketches, released on cassette via Ragoo Records, Luzee builds a quiet but radical bridge between distant worlds. African and South American field recordings, analogue machines, boom-bap discipline and independent beat culture converge into a process that feels closer to sonic archaeology than to production in the conventional sense.

Old recordings are not sampled for effect, but studied, respected, and carefully reactivated—reassembled into beats that retain their weight, their imperfections, their human density.

The choice of tools matters here. Digital waves meet analogue workflows: not nostalgia, but method. It becomes a way to slow down, to stay physically connected to sound, to resist the frictionless logic of platforms and endless streaming. In Luzee’s practice, listening is not passive consumption: it’s commitment, repetition, and attention.

This interview traces the roots of Afro Sketches and the thinking behind it: the synthesis of cultures that never fully disappeared, the ethics of working with inherited sound, the role of instinct in creation, and the quiet refusal of neoliberal music economies that flatten everything into metrics.

What emerges is a portrait of an independent beatmaker operating in the underground not as a pose, but as a position, where resistance takes the form of coherence, autonomy, and care.

If you had to introduce Luzee to those unfamiliar with him, what would you say in three words?

In three words… a beatmaker living in Bologna, perhaps also influenced by that environment. And yes: a producer.

You built Afrosketches using African and South American field recordings, also playing a few instruments. It’s a beautiful rhythmic blend. What was the first beat that struck you so much that you said, “I want to be in this“?

So, it’s a bit of a long story. This tape was born from the desire to pay homage to the musical roots that give rise to the sound I’m most attached to: African-American music, which we listen to and know as hip-hop, funk, and so on.

The spark came from boom-bap. Although I’ve listened to a lot of jazz, there are many connections between the two. Both genres are simplifications of complex rhythms found in various African cultures, particularly Central African ones.

Afrosketches was an idea I’d had for a while, but I hadn’t yet found the right interpretation, due to my respect for that culture, and because I’ve always avoided any form of appropriation.

The interpretation, in reality, was simpler than I thought, as often happens. I tend to take mental journeys and complicate my life, but the most straightforward thing was to reinterpret my journey and my listening through lo-fi beats.

Field recording samples, you almost do archaeology with the drum set, you play with instruments, and you play with suggestions: in some cases, very strong, in others barely articulated. How did you choose what to sample and what to leave a little more buried within the research?

Well, I was guided a lot by instinct…When writing the songs, in some cases, I felt a direct connection with the more spiritual aspects of the music I was working with.

As if it were an ancestral language, capable of speaking to everyone.

From a certain perspective, do you think we can call it sonic anthropology?

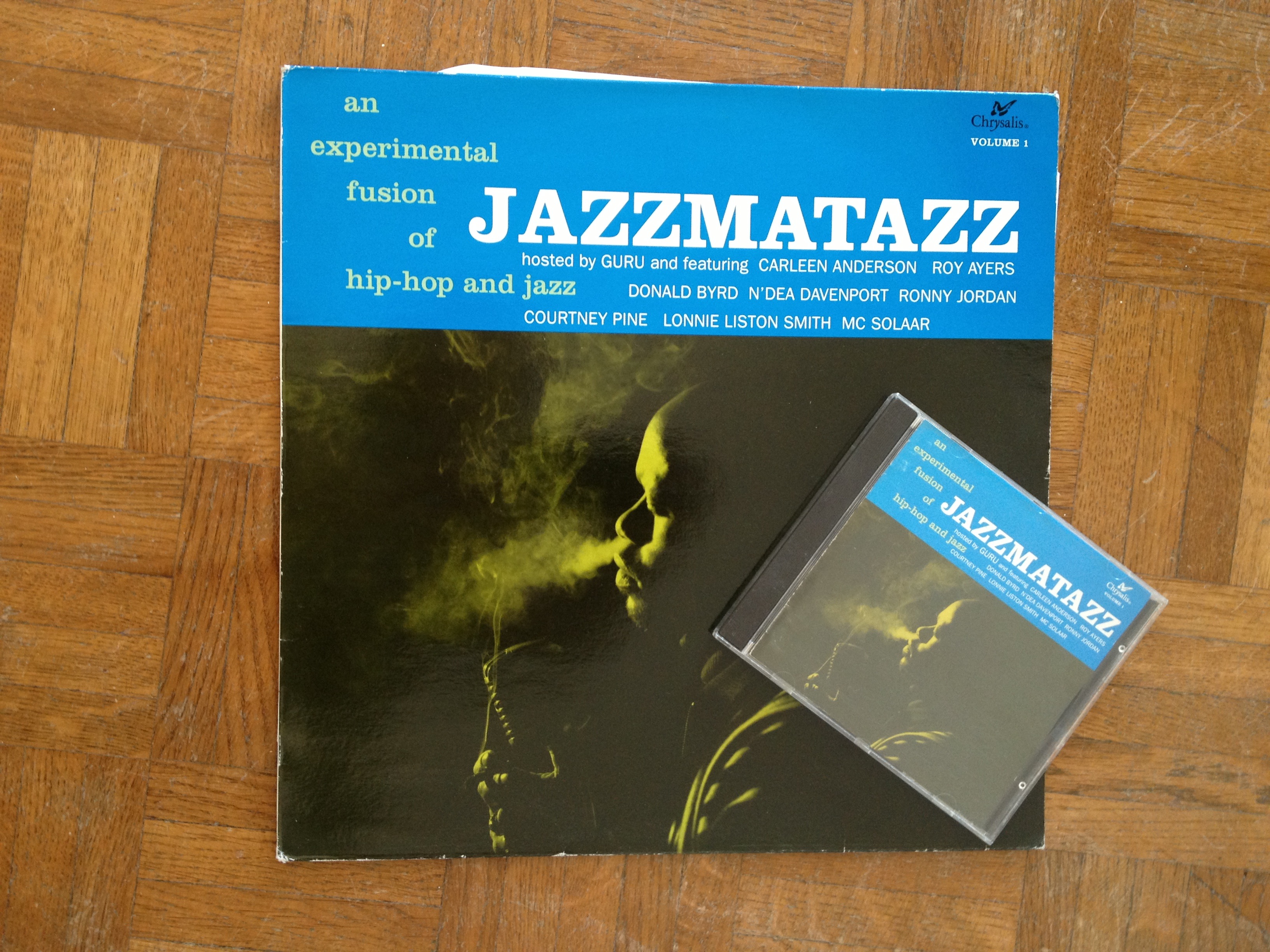

Yes, in a certain sense, it’s an archaeological research. I began with the rhythmic component, which remains the predominant element in the project. Then, I let myself be guided by instinct, “unearthing” records produced between the ’70s and ’80s, which fascinate me immensely.

How much weight does instinct have in your workflow? Is it a competitive trance or a surgical precision in following your curiosity?

Going with the flow without overthinking it opens different doors: it’s not the first time it’s happened to me.

When you’ve had a project idea in your head for a long time, but you don’t put it into practice right away for various reasons, it’s as if it matures within you. When the time comes, everything flows seamlessly, because it’s as if part of the work has already been done, at least mentally.

In the case of AfroSketches, instinct plays a big role in the workflow, particularly in the choices of samples. Then it was also instinctive to choose the drums to use with the samples, so that everything felt natural.

Beatmakers know this: there are times when you spend hours searching for the perfect drum kit, and others when in ten minutes you already have a defined loop or an entire beat. In this case, most of the songs were born in that same short period of time: I didn’t do anything else; I was completely focused on this journey.

What instruments did you use?

Akai MPC One, Roland SP-404, electric bass, Grandmother Moog, and Logic as the DAW. And then a vintage Tascam mixer, which I used to finalise the songs once I had already imported them into the sessions in Logic.

I created stems and dub and “colour” them on the Tascam: excluding some tracks, adding effects… working on them as if they were a final manual pass.

Nerd curiosity: why not work with Tascam first and then digital?

Both because the studio was wired that way—so I had the MPC connected to the SP and then from there to the DAW—and because I didn’t feel the need to tweak the EQ or the mixer’s transformers at that stage.

The desire to play creatively with the music during the finalisation phase was more decisive: not so much for the colour of the mixer’s channels. It was more of a concrete, physical approach: getting your hands on the music, especially at that stage where you usually work with the mouse, add effects, and automate.

What do you mean by “getting your hands on”? Do you mean having an analogue instrument to use?

In a certain sense, you can “touch” the music directly, without getting caught up in the analogue-versus-digital debate, because there’s no way out. I’ve always been pro-both.

Digital is incredibly convenient. Analogue gives you more immediacy, in my opinion, beyond the sound, which is also a very personal thing. I think analogue instruments have a particular creative power because you touch them, you stay focused, and you have fewer distractions.

The sound of the album is “focused,” in fact: I’d say quite material in this sense. How much was it a conscious choice to let the music breathe, even with its flaws?

It was a prerequisite for this work: I wanted it this way, dirty. I like the music not to be too “clean.” Although obviously, I sometimes compose more refined pieces, it depends on the project.

Here, I wanted to follow a spontaneous path. The “flaw,” so to speak, becomes part of the work: it serves to convey to the listener the moment of composition, the feeling.

And this, if you think about it, is also in line with field recordings: they are born as documents of a moment, not as “art” in the classical sense. You are collecting the unrepeatable and then recomposing it into a beat.

What are you trying to say about Afro-descendant sonic memory?

It’s my vision, my reading of this music, of this rhythm that has somehow reached everyone over the centuries. Then it diluted, transformed, changed, but so much music around the world—even here in Europe—has some of its roots in Africa.

For me, it’s a universal and foundational language, one I feel deeply connected to, one that has always resonated with my sensibility. And since it’s music I feel capable of interpreting, I liked to develop this direction in my career.

It also helped me come full circle: I don’t think I’ll make any more tapes like this. It was a moment when I felt the need to express my vision on this subject.

As a European beatmaker, dealing with sound archives that speak of identity, survival, and struggle, how do you position yourself with respect for this gigantic legacy, beyond the purely sonic aspect?

With respect for the observer and for those who want to help relaunch something. It’s a huge and very delicate issue.

When we talk about struggle and identity, I believe that—albeit on a smaller scale, in different forms, and without inappropriate comparisons—if we remain on the level of ordinary people, our ancestors also found themselves struggling. They had to lose rituals and habits to improve their condition. These are stories found everywhere.

In this sense, certain issues resonate everywhere, even if they then take on different and undeniable forms, weights, and consequences.

I come from a tiny village in Abruzzo; I’ve lived in Bologna for many years, but I was born and raised in the countryside. My grandparents’ stories—of the war, of oppression—are sobering experiences, and part of a widespread feeling.

What is the most difficult and invisible part of a process and a project born quickly?

Definitely the compositional choices, because that’s often where the most time is wasted. Having a clear objective and the awareness of having to decide quickly is a challenge.

In undertaking such an instinctive project, the technical experience gained from more complex and thoughtful projects also helps: it allows you to focus more on the creative aspect and less on the operational one.

And what changes in your mind, in your work, when the beat is for you and not for others?

If we’re talking about others—singers or rappers—there’s less work than when the beat is for me, because I have to say everything: I’m not just a part of the project.

When you collaborate with someone, you must know how to leave space for creativity, so that the other person can express themselves freely. I’ve always worked collaboratively with artists, defining direction and sound together: it’s never been a process like “Okay, I’ll make a beat and send it to you.“

I’m a musician, coming from the world of live bands: for me, music has always been about relationships. Doing it alone was a wonderful discovery, because I could finally explore what I wanted. But as a solo artist, there’s a greater level of responsibility: you have to expose yourself 100%.

Afrosketches is released on tape via Ragoo Records: what does a work like this on tape gain, and what does it lose—if it loses?

In my opinion, it gains because it’s a physical format: so it’s something that endures even beyond the expansion of streaming services.

What’s your relationship with streaming?

I don’t like to demonise technology, because I’m a nerd and I’m passionate about it. The real issue, however, is who controls these technologies. It sounds like a movie quote, but if today they’re in the hands of neoliberal capitalism, for me, that’s a huge problem.

It’s incredibly convenient to have access to nearly infinite catalogues everywhere: twenty years ago, it was unthinkable, and that’s a wonderful thing. However, from an economic and ethical standpoint—and I’m speaking as an artist—there’s a serious issue.

Personally, I cancelled my Spotify account about a year ago. I started almost as a challenge, and I have to say I don’t miss it. I started buying music again, digging on my own, and I’m happy with this choice.

Beyond political or ethical reasons, I realised I had almost stopped researching music. I had become passive in my listening, because a pA platform like Spotify profiles you: once profiled, it locks you in a bubble and endlessly offers you very similar songs. At first, it seemed positive, but then I realised I was getting lazy.

And it’s the same mechanism as scrolling through Instagram like a fool, watching pointless reels—which I do, I realise—but which I also recognise as toxic: ultimately, it’s a waste of time and a form of intoxication.

Now I listen to less music, quantitatively, but I go looking for it: on Bandcamp or elsewhere, whenever I want. With my monthly budget, I also buy digital records, not just vinyl, and I’ve regained a personal library that’s mine: on my hard drive, on my computer, which I can listen to over and over again whenever I want.

And I can also listen again because it’s my way of experiencing music: even though I’m a newbie in beatmaking, I’m not very young. I grew up in the ’90s, so I have that approach where you listen to records over and over again: you don’t “rent” them, you own them.

It’s a generational thing, without saying whether it’s better or worse. That’s what I do: I listen to records over and over again.

Speaking of Afrosketeches, Nicola Giunta’s artwork adds a very strong, almost—I’d say—ritual imagery. How does it interact with the sound world you’ve created?

Nicola is a very talented artist who works with Xerox Art, which I discovered is a practice created using scanners. So it’s a sort of collage.

He listened to the record and immediately understood the direction to take, focusing on the imagery. We exchanged some ideas, he made several suggestions, and we arrived at an image that truly has that ritualistic approach that, in my opinion, is also perceived in the sound of the record.

After a project like Afrosketches, where do you feel your sound is going?

I’m not sure exactly. Lately, I’ve been focusing on making beats for rappers and singers, so I’m moving in a more “production” direction, even quite hip-hop-oriented.

What are your latest listens? Do you have any recommendations for our followers?

I want to recommend an artist named Dele Sosimi, whom a friend, Lorenzo, recommended to me a few years ago. He’s an Anglo-Nigerian Afrobeat artist: I’m obsessed with two or three of his albums, which are truly beautiful. It’s music that puts you back in order, songs that bring you well-being, no matter what happened during the day.

I’m also listening to a lot of Ruben James, who released an amazing album, Big People Music. And Boldy James’ latest album with Alchemist: there’s a single called Business Merger, which is beautiful.

What’s the one question you never want to be asked?

It would be a very embarrassing question, obviously.

A greeting to the nation, and then we’ll let you go. Whatever you want.

Please, let’s get off these damn social media; they’re making us all stupid.

Thank you, Luzee, and good looking out. If you would like to learn more about the man and his music, just fly to Ragoo Records’ Bandcamp page and dig for yourself.