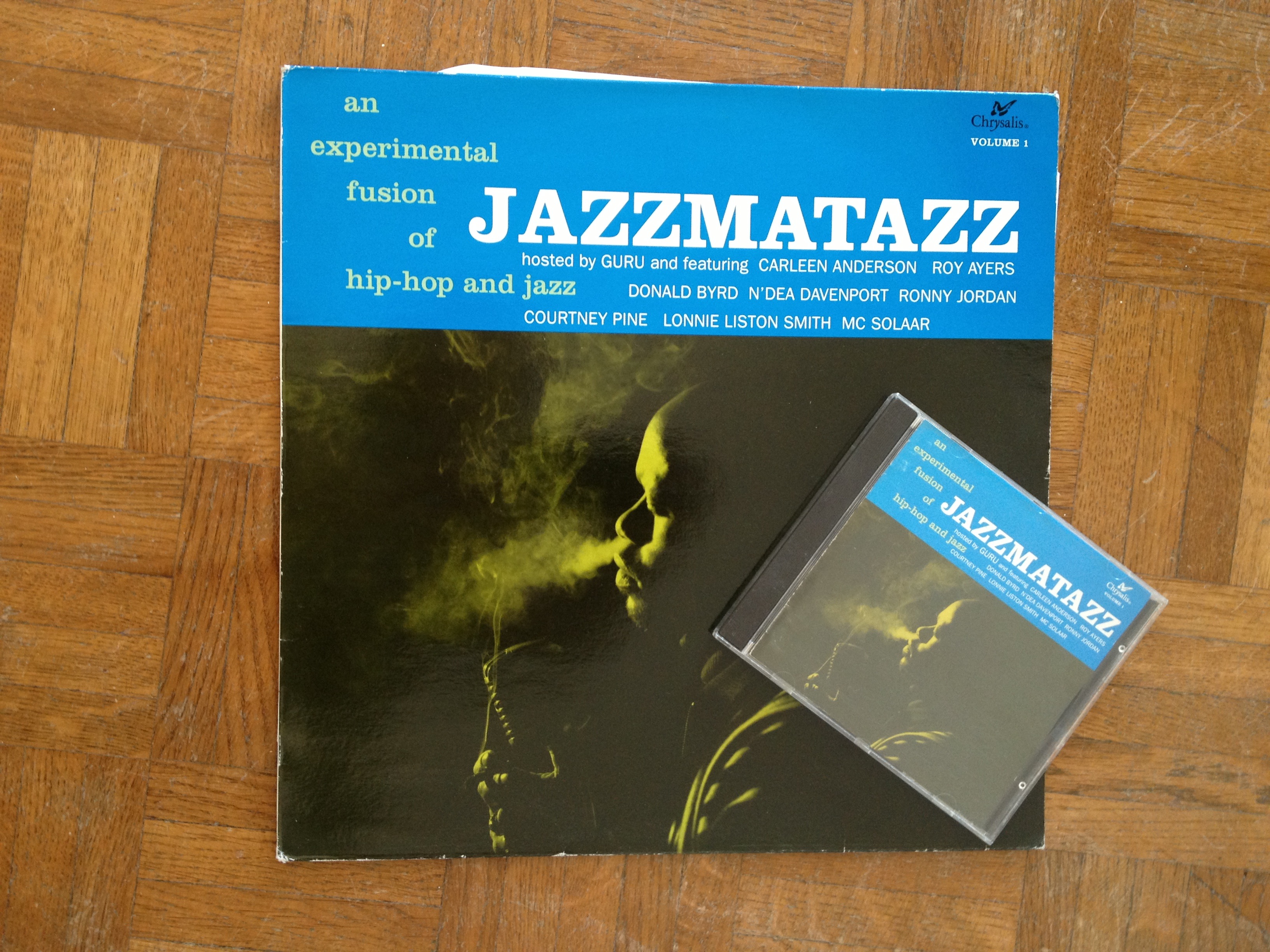

Twenty years ago today, Guru’s own Jazzmatazz dropped. Then, everything changed.

The first thing I wouldn’t like to write but I’m forced to, is that time runs faster than you know and changes your perception of itself too. It’s funny how twenty years ago I used to look at twenty years before like it was some light years before, and now I see twenty years ago like two weeks ago. Sorry, unpromising incipit. Let’s try better.

Whatever – 1993 was my last year of high school, my real introduction to the emcee practice, turning eighteen, breezin’ the best days of my life without much knowledge to it. And it was somehow inebriating, living with no tomorrow well-fixed yet. Fascinating. And the music was perfect for those times.

The spring of 1993 was crazy. So many hot records were poppin’, and, due to geographical problems, poor distribution and NO INTERNET, we were often struggling to have a dubbed cassette or an actual copy of many of these records, since it was impossible for many of us to be on track upon the release date.

Sometimes, you were supposed to catch a record months after the real dropping date. Or years, depending on the buzz the local press and the retailers were giving on such records or not. Then you were supposed to dig or just wait to be put on some serious heat, sometimes. Another century, another world.

So many game-changing records came out in 1993. Wu-Tang emergency came up with Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), Black Moon released Enta Da Stage, a young Snoop Doggy Dogg went Doggystyle, just to name a few. The list could go on for a while, so do your own research if you’re not up to it, you will discover tons of great music.

Yet among this whole American record industry madness, in these days where hip hop was tremendously growing and changing itself and our lives, worldwide, there was another swinging revolution going on. In Europe, since the late Eighties, early Nineties, there was a certain funk and soul-jazz renaissance, led by several UK groups and labels, such as Gilles Peterson’s own Talkin’ Loud.

The man you probably know for his Worldwide show on BBC One, back then was in charge of inventing the term acid jazz as we knew it. Most UK musicians were looking at the Seventies sounds from jazz and funk records, revamping those grooves and recreating them with some more electronic-infused formulas and equipment, fueling the rare grooves madness that in the U.S. was contemporarily brought to the next level by producers and diggin’ pioneers such as Pete Rock.

Around that time, especially in New York, the early Nineties brought what we know as jazz rap. Gang Starr, the famous duo formed by Dj Premier and Guru, came up first with a lot of jazz samples on their compositions, as many others in their era did (such as Pete Rock, ATCQ, De La Soul, The Roots, etc.), but they have been possibly been retained as the true champions of this musical wave because of their seminal hit Jazz Thang, originally commissioned by Spike Lee for Mo’ Better Blues soundtrack, also featured on Gang Starr first album.

The things were moving fast, there was a fever for more jazz, fueled also by the Native Tongue collective success, and lots of old and obscure jazz records were discovered, sampled and broke from deejays and producers worldwide. I can remember we were all trying to swing a little jazz and play some extra sound, sometimes getting in trouble with our parents for snatching some good oldies, for instance, as my man Jah Rebel could easily testify.

But, all in all, the real thing was still to come. The real thing was letting real musicians play in-studio sessions with producers and beatmakers, while emcees would flex their rhymes over those beats. The man who did it first and better, who brought an all-star line up of jazz musicians in-studio to realize this, was the one known as Gifted Unlimited Rhymes Universal, the G.U.R.U. from Gangstarr, who conceived and realized Jazzmatazz volume One.

The album dropped this week, May 18th 1993, exactly twenty years ago.

At that time, having in-studio musicians like Donald Byrd, Courtney Pine, Roy Ayers, Lonnie

Liston Smith, Ronny Jordan, Brandford Marsalis, singers such as N’Dea Davenport and DC Lee, and the French star Mc Solaar, that was huge, man. The first real fusion of jazz and hip hop, live instruments meeting drum machines and rappers, creating an organic ensemble of great music.

The impact the record had on our airwaves and lives was as huge as this lineup. I started playing the first single, No Time to Play, in heavy rotation on my radio show, but the whole album was incredible, and possibly the single just the head of an iceberg of coolness. So I ended up playing it all, track by track, plenty of times.

The hard drum programming, handled by Guru himself, was blended with superlative yet simple executions from the aforementioned musicians, and the whole fusion was the perfect scenario for Guru’s haunting voice, delivering inner-city tales effortlessly, stumbling over words and tones with a natural pace. The King of Monotone, as he dubbed himself, was possibly at his best of the first period of his production, and the result was awesome. Rolling grooves defy time and space, and twenty years later the set is still fresh. Impossible to highlight one piece instead of another, since the whole set a new standard in music, creating premises for several episodes that followed, but never surpassed the first instalment of the series.

This is just an invitation to listen to this great album, once again, and to avoid the loose time, as there isn’t any to play, you know it.

Out like them good old days.